Update as of May 26, 2023

Are you “Team Warhol” or are you “Team Goldsmith”?

Well, that probably depends on whether you are a photographer who is interested in maintaining strong copyrights to your wares. It appears that the U.S. Copyright Office (CO) is on Team Goldsmith, as indicated by their amicus brief filing submitted to the US Supreme Court in the case Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, where arguments will be heard on October 12, 2022. Let’s go over the background leading to this SCOTUS case.

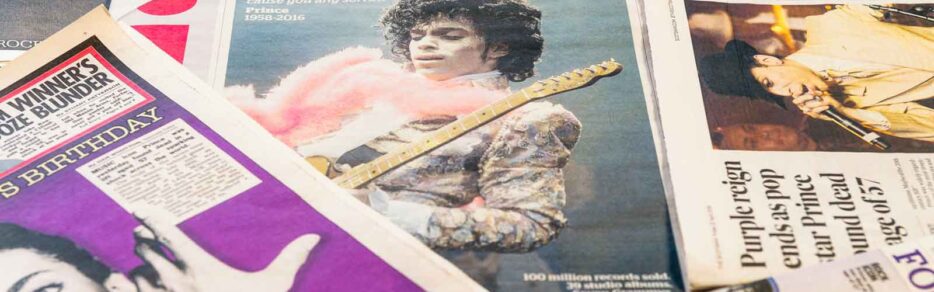

The Back Story on Goldsmith’s Prince Photo

In 1984 Vanity Fair licensed one of Goldsmith’s photos of Prince, shot in December 1981, for $400 to create an illustration of Prince to be used in an article “Purple Fame.” Vanity Fair did not inform Goldsmith that the photo was being used by Warhol as a reference, and she did not see the article when it was initially published. On April 21, 2016, at the age of 57, Prince died. The next day, on April 22, Condé Nast, Vanity Fair’s parent company, contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF). They were interested in producing a commemorative issue on Prince and wanted to use the 1984 image. Condé Nast obtained a license and published the tribute magazine, which carried a Prince Series image on an orange background on the cover in May 2016. The image was credited to the Foundation, and there was no mention of Goldsmith in the attribution. This is when Goldsmith discovered how her photo was used.

The Prince Series

This is also when Goldsmith discovered that Warhol had created 15 additional artworks based on her black & white studio photograph. This was known as the “Prince Series.” She informed AWF in late July 2016 that the artwork had infringed on her copyright. In November 2016, Goldsmith had her Prince photo registered with the copyright office as an unpublished work. On April 7, 2017, AWF launched “preemptive strike” against Goldsmith by suing her before she had a chance to file a copyright infringement lawsuit first. AWF wanted a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or, in the alternative, a ruling that stated that the Prince Series was a fair use.

What Factors Are Used to Determine a Fair Use?

Copyrights give owners the exclusive legal right to reproduce, publish, sell, or distribute an original creative work or to make a derivative work. However, there are times when you can use the works of others without their permission, it is called a fair use which is a defense against infringement. There are four statutory factors that courts use to determine when unauthorized use of another’s copyrighted material is a fair use:

- the purpose and character of your use

- the nature of the copyrighted work

- the amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and

- the effect of the use on the potential market

District Court Ruling on Prince Series

Judge John G. Koeltl of The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York found fair use and based its decision on the belief that: The Prince Series was transformative as Goldsmith’s photo shows Prince as “not a comfortable person,” the Prince Series shows the singer as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.”. “In creating the Prince Series, Warhol “removed nearly all [of] the [Goldsmith] [P]hotograph’s protectable elements.” He also stated that the Prince Series works “are not market substitutes that have harmed – or have the potential to harm – Goldsmith.”

Goldsmith Appeal

Goldsmith appealed her loss to the 2nd Circuit Court, which disagreed with the District Court. “[W]e feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that ‘each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a Warhol,’” the appeals court points out. “Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.

(1) An artist must do something more than merely apply their unique style to an unlicensed work in order to constitute transformative use.

(2) An artist’s subjective intent, even if it was to create new artwork with a different message or meaning, is irrelevant to the question of transformativeness.

(3) Likewise, a critic’s or judge’s personal assessment of the meaning, intent, or impression of a new work may not be relied on to determine if that work can be reasonably perceived as having a new message or meaning.

The lower court erred in both finding the Prince Series transformative, and that factor one favored fair use because: (a) the different Warholesque aesthetic of the Prince Series is irrelevant; (b) the Prince Series retained the essential elements of Goldsmith’s photograph without significant additions or alterations, and (c) the lower court improperly based its decision on a stated or perceived intent of Warhol rather than on the reasonable perception of the Prince Series.

“What this case does is recognize the conflict between the right to control derivative uses of the work and how that overlaps with the transformative use factor in fair use analysis,” “The other significance of this case relates to the fourth factor with the court making clear that the burden of showing no harm is on the user and the Warhol Foundation didn’t show that there was no harm to the photographer.” The District Court incorrectly had the burden on Goldsmith. While the Second Circuit agreed with the lower court that the actual markets for the Goldsmith Photograph and Warhol’s Prince Series works may not completely overlap, the court still found that this factor also disfavors fair use because it found harm to Goldsmith’s potential licensing markets, including through the evidence that both Goldsmith and Warhol licensed their Prince images to print magazines with overlapping customer bases for articles about the musician.

What Is “Transformative” Art?

AWF petitioned for certiorari to the Supreme Court, which granted it. The question presented is: Whether a work of art is “transformative” when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material (as the Supreme Court, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, and other courts of appeals have held), or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it “recognizably deriv[es] from” its source material (as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit has held). Basically, AWF wants their transformative art to be considered a fair use.

The amicus brief filed by the CO supports Goldsmith’s position and states that the judgment of the 2nd Circuit should be affirmed, i.e. that Warhol’s use was not a fair use. The CO stated that the fair use inquiry is necessarily use-specific and that the analysis should focus on this particular use, AWF’s 2016 commercial licensing of the Orange Prince image to Condé Nast. This allegedly infringing use served the same purpose, depicting Prince in an article about him published by a popular magazine, for which Goldsmith’s photographs have frequently been used.

AWF argues that the first fair use factor supports fair use here because the Orange Prince image conveys a meaning or message that is different from that of the Goldsmith Photograph. According to the CO, treating this purported difference as sufficient under Section 107(1) would dramatically expand the scope of fair use. The CO also argued that the fourth fair use factor strongly supports the 2nd Circuit’s conclusion that AWF’s use was not fair. AWF’s commercial licensing of the Orange Prince image to a popular magazine undermines Goldsmith’s ability to license her photograph, either for inclusion in magazines or as an artist reference to facilitate the creation of derivative works. This type of harm to photographers would be magnified if uses like this one regularly occurred.

Art is What You Can Get Away With

The outcome of this case could have a significant impact on the strength of photographers’ rights to their work as well as impacting transformational pop artists like Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol has been quoted as saying: “Art is what you can get away with.” Andy Warhol may have gotten away with it in his lifetime, unfortunately, his foundation may now be paying the price for it!

Pittsburgh Intellectual Property Attorney

Kathleen Kuznicki works with her clients to determine their best strategy for IP protection. Contact her via email at kkuznicki@lynchlaw-group.com or call our office at 724.776.8000.